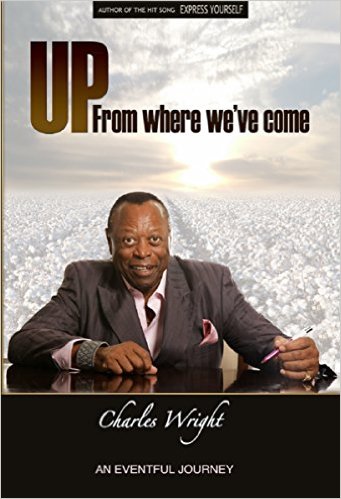

Music hardly receives a mention in Up From Where We’ve Come, the first volume in memoir written by Charles Wright, the long-time front man of Charles Wright & the 103rd Street Watts Rhythm Band. The autobiography covers Wright’s childhood growing up as one of 11 children born the Edmund and Magnolia Wright in and around the Mississippi delta town of Clarksdale.

Music hardly receives a mention in Up From Where We’ve Come, the first volume in memoir written by Charles Wright, the long-time front man of Charles Wright & the 103rd Street Watts Rhythm Band. The autobiography covers Wright’s childhood growing up as one of 11 children born the Edmund and Magnolia Wright in and around the Mississippi delta town of Clarksdale.

This would seem odd to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the history of Mississippi delta and the town of Clarksdale in the history and formation of what became known as blues, R&B, soul or gospel. However, Wright is a guy who – as they say in those parts – can spin a yarn. He’s also a pretty good writer, so the story that he has to tell sings in its own way. The story told in Up From Where We’ve Come is more about the Wright family – and specifically about the patriarch and matriarch of his sharecropping family – than about the soulful baritone who enlivened the late 1960s and 70s with classics such as “Loveland” and “Express Yourself.”

Charles Wright is there and he had plenty of adventures as a young boy in the segregated Mississippi of the 1930s and 40s. However, Wright’s first person presence in this book allows him to take a sociological view of a system that exploited and brutalized black people and the casualness of that brutalization and exploitation.

That violence was emotional, physical and financial in nature and it impacted the relationship that blacks had with the whites who owned the farms where African-Americans toiled as tenant farmers. However, that violence wafted in the atmosphere around the intra-racial relationships as well, and they explain why music makes only fleeting appearances in this book. A vivid example comes around the midway point when Charles accompanies his father into town. Charles remains in the car that his father has purchased – cars play a major role in the exploitation of the Wright family – and he hears the blues of Sonny Boy Williams flowing from a blues joint owned by his aunt.

Young Charles, transfixed by the music, begins to pat his feet, bob his head to the melody and move – forgetting that blues music and especially the world occupied by his Aunt Sissy are forbidden by his preacher father, who smacks his son out of his reverie. Edmund not only fears eternal damnation, but the kind if casual violence inflicted on patrons of Sissy’s joint. It’s the kind of violence employed to redress slights and defend honor, project machismo that is called “black on black” crime today. Wright reminds us that this kind of violence is as old as the brutalization found in places such the Mississippi delta in the 1940s.

Wright may have eventually found his singing voice had he remained in the delta, as generations of soul men and women discovered their gifts there. However, he probably would not have been the front man of a funk group with the lengthy and unforgettable name such as the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band, and the story the enlivens this memoir that reads like a novel is how his parents – after more than a generation of exploitation at the hands of a system that is a small step about slavery – mustered the courage to move their family more than 2,000 miles from the delta to Los Angeles.

The spiritual trek made by his father – a man wracked by bitterness, self-doubt and fear – is especially poignant. Wright loved his father, but the two had a complicated relationship. As a boy, Wright was often on the business end of discipline meted out by Edmund Wright. However, Charles also saw his father repeatedly exploited and mistreated by the white planters and merchants and that had the boy’s perception of his father. Still, Edmund Wright conquered his fear and boarded a train with his sons to follow his wife and daughters to LA. The book’s final scene is one that illustrates how Mississippi’s racial caste system crippled people: Edmund looks for the colored section of a train that has left the deep-south and moved into the part of the country where Supreme Court rulings outlawing segregation in interstate travel were the law of the land, is poignant and sad, and mark’s a pivotal moment in the young man’s life. It is truly touching, and sets the scene for the second volume that one can only hope is as compelling. Recommended

By Howard Dukes